Weather 101: Why does high pressure bring good weather?

For the rest of the week, the area will be under a strong area of high pressure, giving way to sunny skies and consistent above-average temperatures.

With the weather calm and temperatures consistent, it seems right to focus today’s weather 101 spotlight on the driver behind this week’s weather.

While featured prominently as a blue “H” on weather maps, high pressure is typically regarded as the less notable pressure system, due to its lack of inciting significant weather events. Highs act as the chef of unremarkable, calm weather patterns, all thanks to the dynamics of wind within the atmosphere.

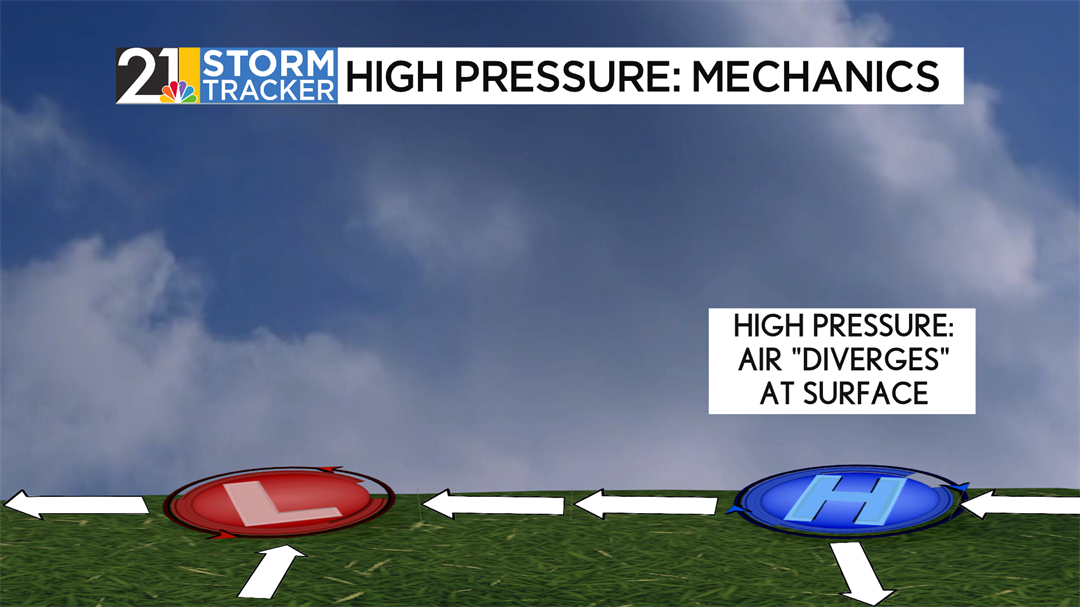

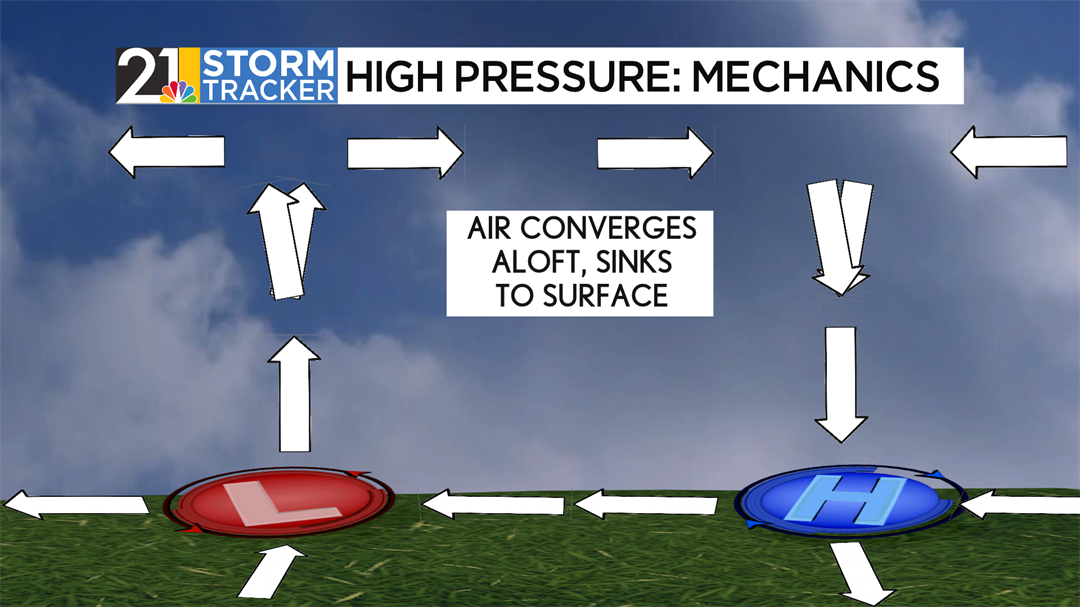

High-pressure systems feature diverging air at the surface, or air spreading away from a point in all directions. Due to the Coriolis effect, air spins clockwise around the system. This means if someone were due east of the center of a high, then they would likely experience winds from the northwest, both away from the center and in a clockwise direction. With air escaping from a point, there must be more air coming from somewhere to replenish the supply. This is how air converges, or comes together, aloft above the center of circulation, and sinks towards the center of the surface high.

Looking at a cross-section, you can equate this to a fountain. Water is coming from above and flows down until it hits the surface, which scatters all over the place. For context, low-pressure systems work on the opposite philosophy, with converging air at the surface and diverging air aloft. This will be covered in-depth in tomorrow’s Weather 101.

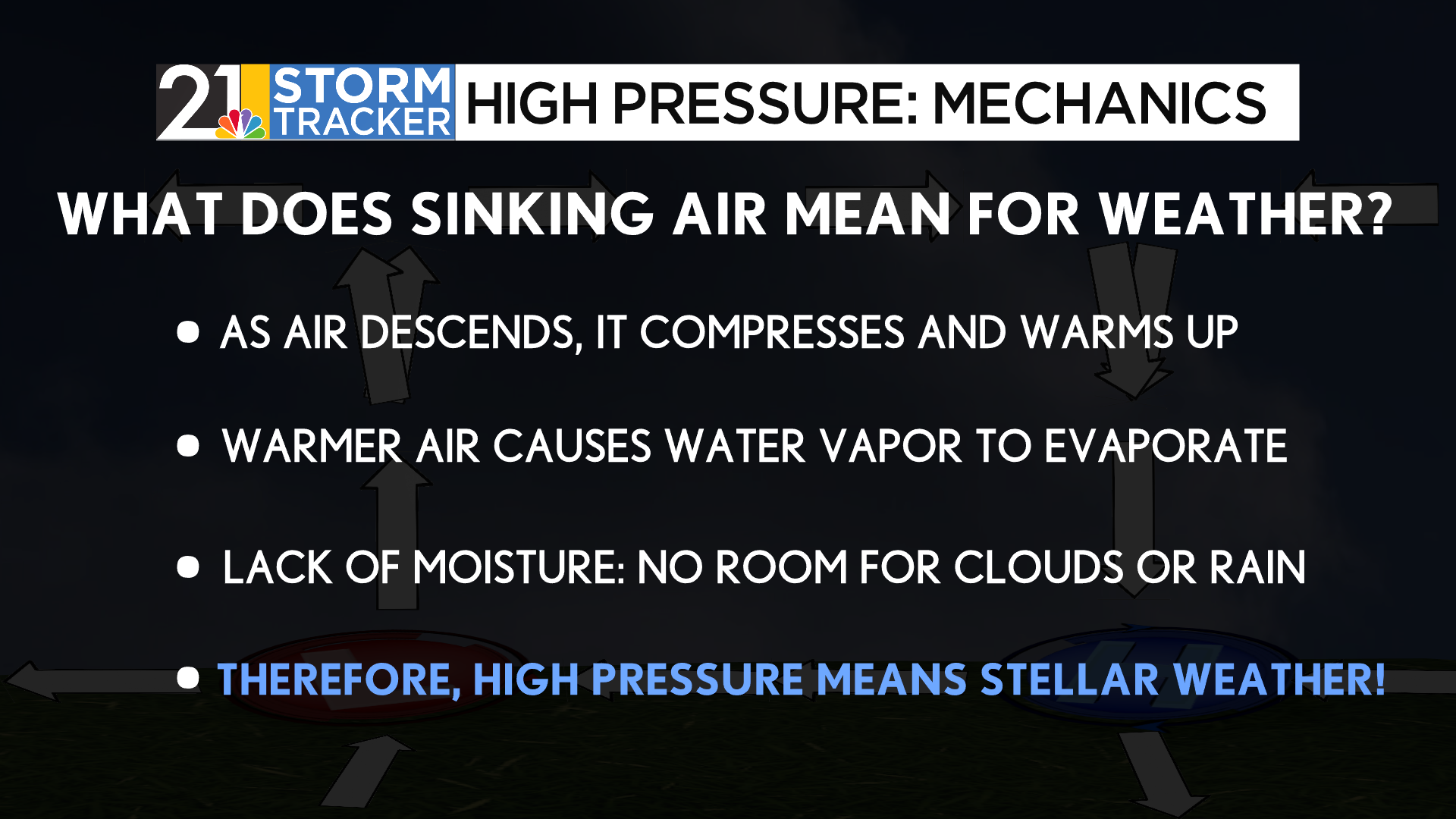

How does calm weather come from a high-pressure system, though? It all comes in the way air moves between elevations. In this case, air sinks from above, and as it sinks, pressure increases, compressing and warming the parcel of air. As the air warms, it dries out and evaporates the parcel. With dry air, there’s no room for rain, or clouds for that matter, to form. This is the basis for why dry weather can be attributed to high-pressure systems.

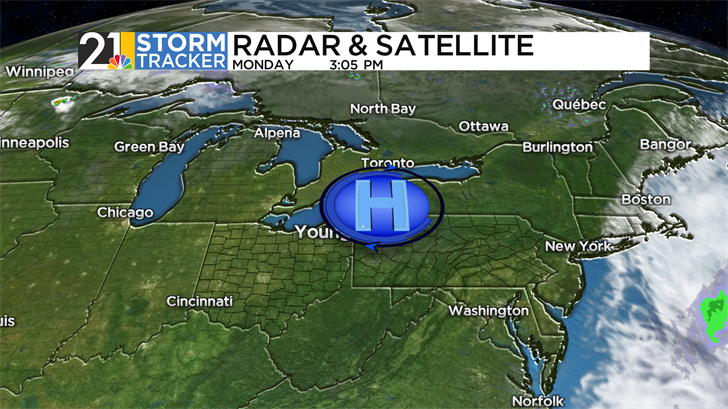

High-pressure systems, much like lows, can be seen easily by meteorologists. Strong highs can whisk away clouds for hundreds of miles. Take today’s satellite picture, which is attached above. The center of circulation, located near Buffalo, New York, is surrounded by hundreds of miles of clear skies, with the closest clouds in Canada and off the Atlantic Coast.

While highs are well-known for producing basic, rudimentary weather, let’s investigate other ways they can impact the forecast. Because clouds are hard to get within these systems, this eliminates the “blanket” that traps ground heat overnight. This is a process called radiational cooling, where heat absorbed into the ground during the daytime can escape back into the atmosphere, uninterrupted. This can cause temperatures to go down quickly overnight and produce volatile temperature swings of over 30 degrees over a day-night cycle.

If radiational cooling works well enough, the temperature can get low enough to create fog, which is another side effect of high-pressure systems.

High pressure is known to make lapse rates, or the change in temperature with elevation, negative. (see more information about lapse rates here.) This is known as a temperature inversion, where temperatures increase as altitude also increases. Air pollution is a frequent issue under inversions, as pollution from humans or other means essentially gets “trapped” underneath a dome of higher temperature air.

High pressure was overhead during the East Palestine train derailment on February 3rd, 2023, and made a notable impact as an inversion trapped pollution in the lower atmosphere. This caused several residents in the town to be evacuated.