Weather 101: How do we measure temperature?

In the late stages of September, summer lovers are rejoicing as high temperatures have been regularly topping 80° around the Valley.

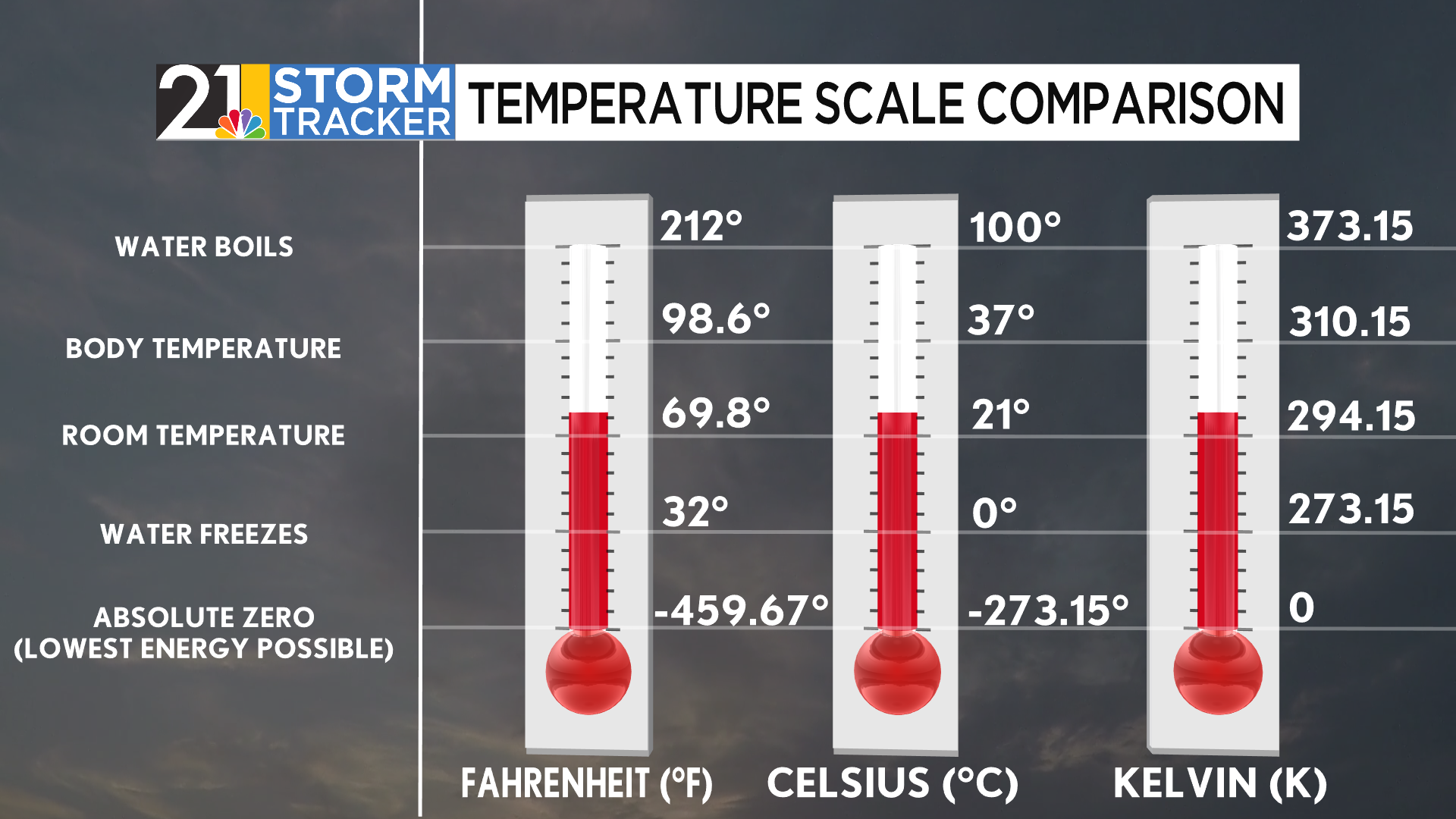

However, some foreign folks might be satisfied with today’s highs in the upper 20s. Some may even find comfort with temperatures as high as 300.

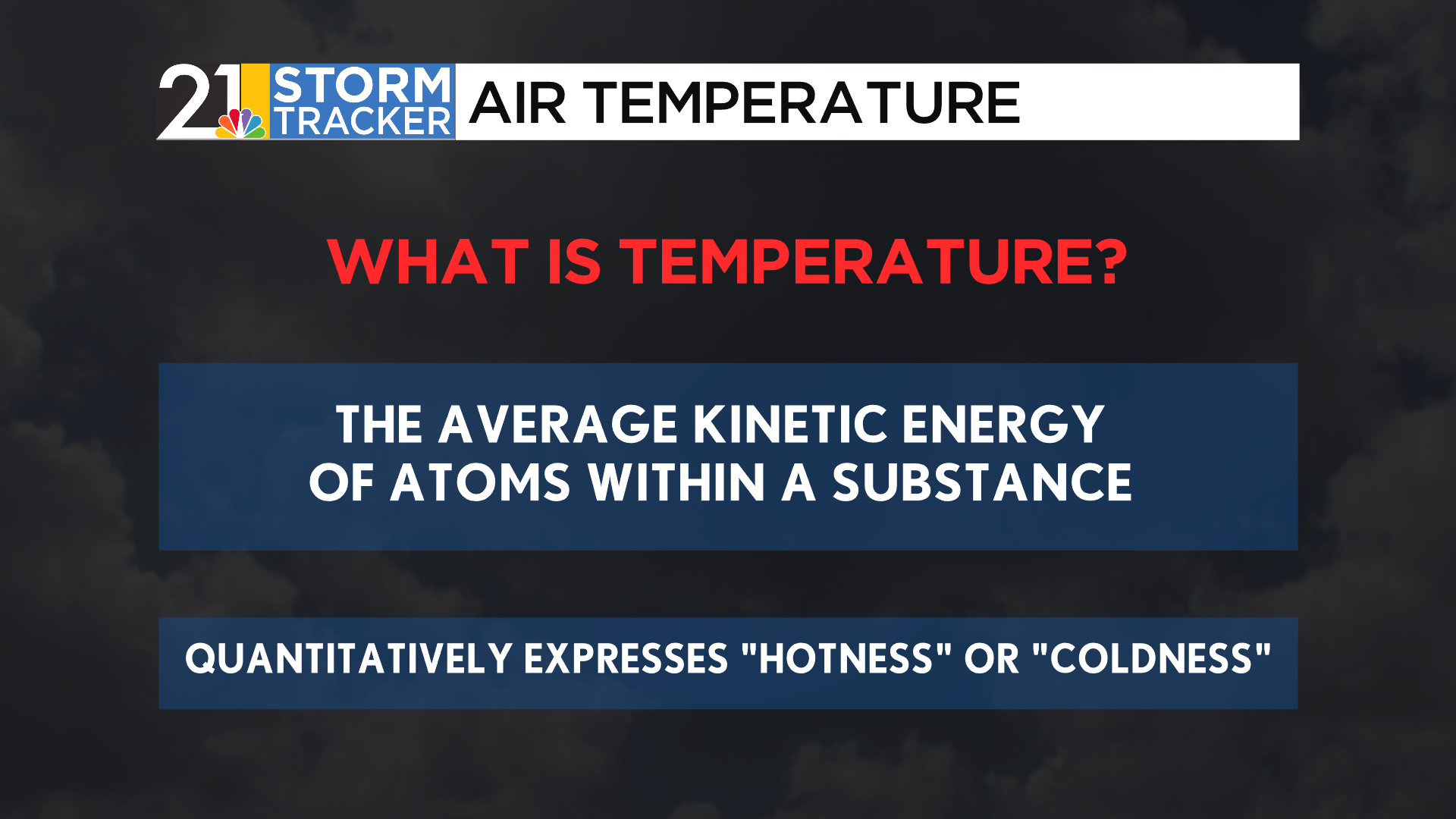

While all three of these temperatures contained wildly different numbers, they each expressed the same qualitative story- a warm, early autumn day, just on different temperature scales. Each of these scales tells the same story: temperature, which is scientifically defined as the average kinetic energy, or energy due to motion, in a substance. Increased kinetic energy means a higher temperature.

A common misconception: Temperature itself is the best teller of whether an object is “hot” or “cold”, though because it is a measurement, we cannot say that temperatures themselves are “hot” or “warm”, rather that high temperatures are making conditions “hot”.

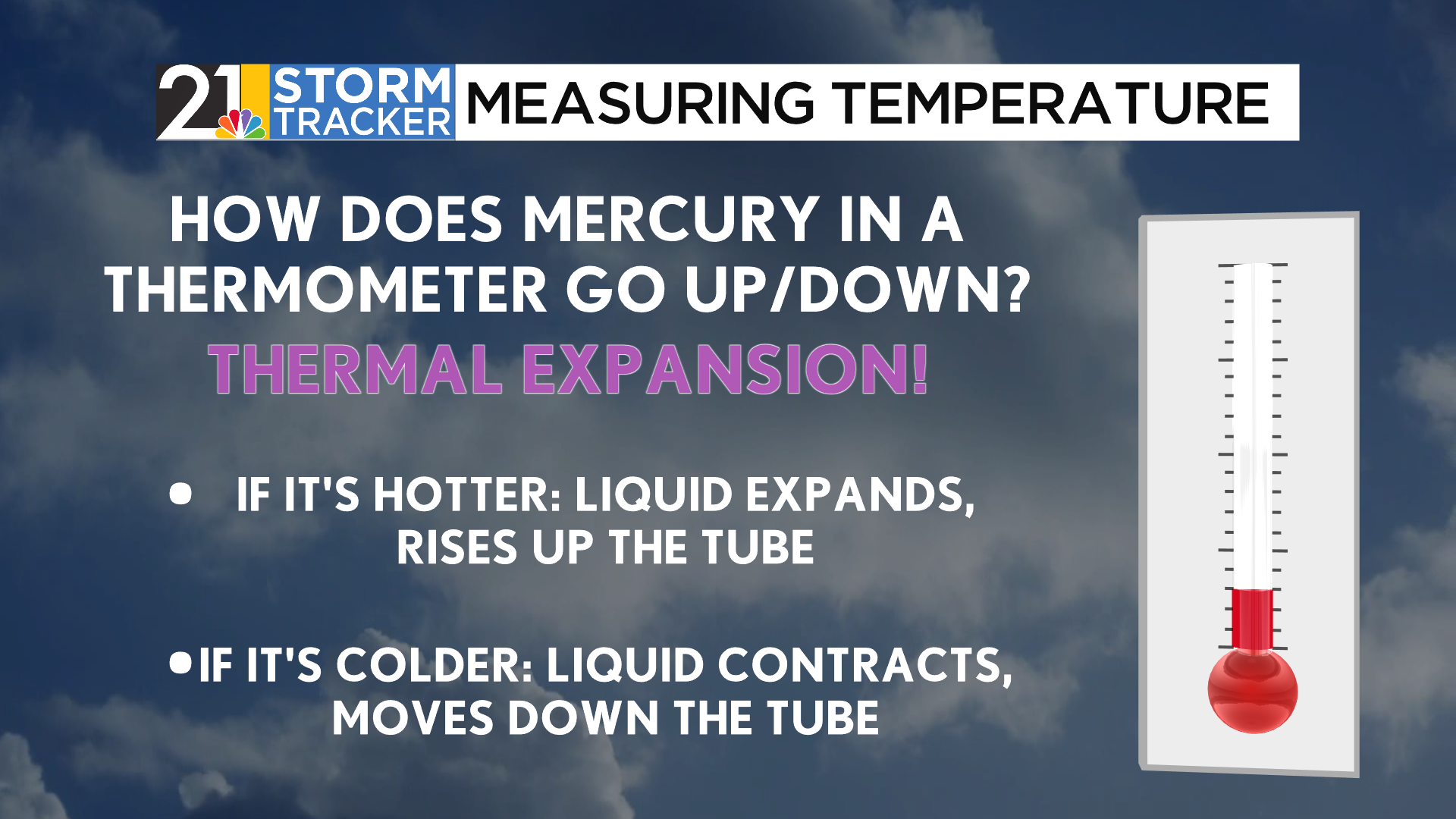

How can we measure temperature in the first place? In the days before electronic thermometers, scientists relied on the principles of thermal expansion to determine the temperature. As the mercury inside the thermometer warms, the kinetic energy within the liquid increases, allowing the liquid to expand. Similarly, as the temperature lowers, the liquid contracts, which brings its appearance down lower in the tube.

Across all reaches of the world, the liquid within the thermometer will expand and contract at the same rate. Through the years, though, different people have created independent ways to determine the numeric value of temperature. Several dozen scales are in use, though there are three scales most commonly used in the world today.

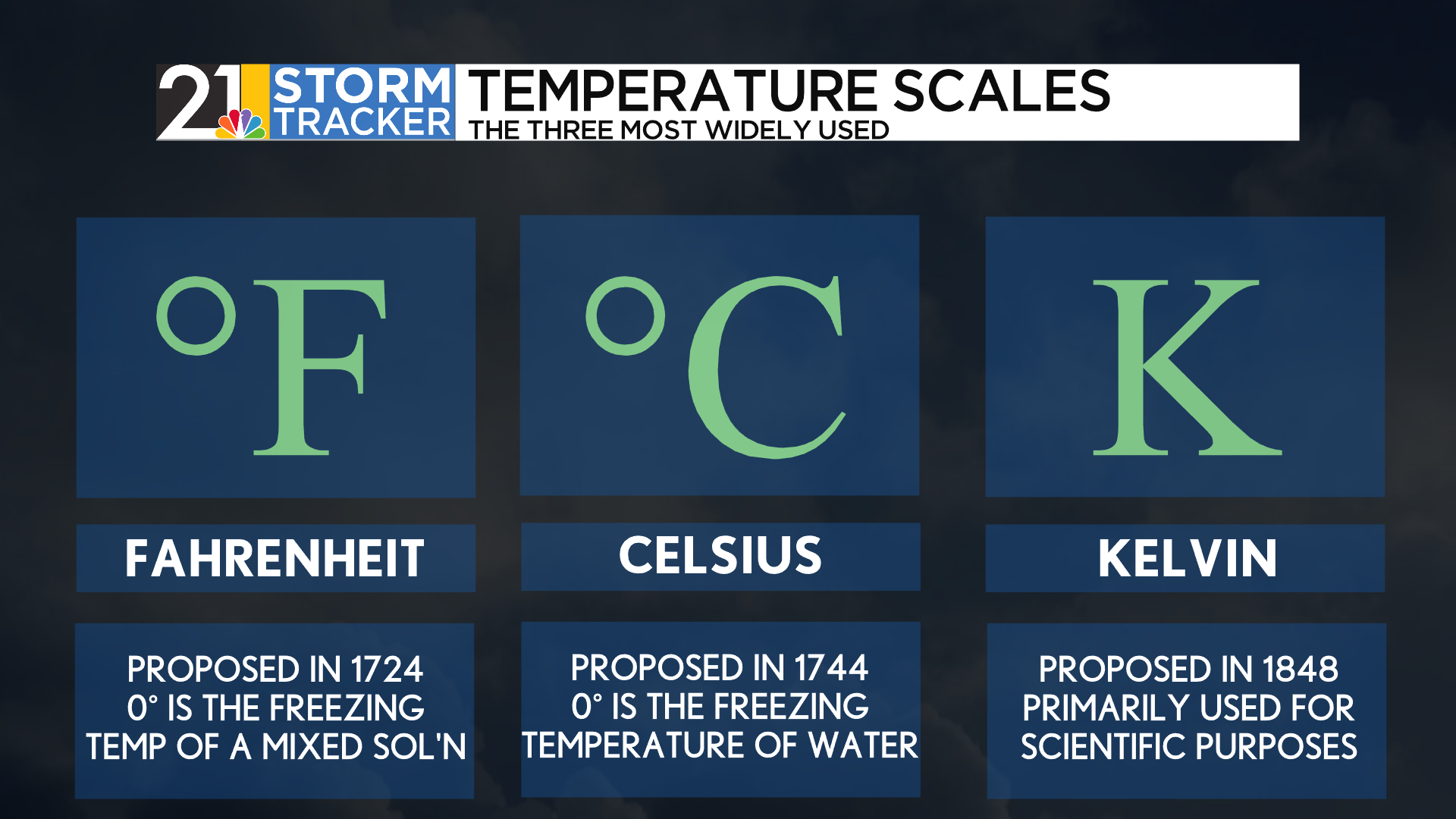

The Fahrenheit scale was developed in 1724 by physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit. It is the most commonly used scale in our corner of the world. The physicist used a lower benchmark temperature of 0°F to describe the freezing point of a brine mixture composed of water, ice, and ammonium chloride (a type of salt). He used an upper benchmark of 96°F (later revised to 98.6°F) for the typical human body temperature.

A major reason why all but two countries use the Celsius scale is that both benchmarks are more realistic and symmetric. This scale, proposed in 1744 by Anders Celsius, describes 0°C as the freezing point for water and 100°C as the boiling point for water. Between the mid- to late-1900s, most countries using the Fahrenheit scale switched to Celsius. The United States even tried and failed in its own act in the 1970s. A degree Celsius is equal to 1.8°F.

The reason you may not have heard of the Kelvin scale is that it is primarily used in scientific settings. This scale, defined by Lord Kelvin in 1848, defines “absolute zero” as a point where kinetic energy in a system cannot be any lower. While containing the same “spacing” as the Celsius scale, it is shifted by 273.15 degrees to account for the change in the zero benchmark. This means that zero degrees Celsius is equal to 273.15 Kelvin. Notably, Kelvin is the only scale of these three that does not implement the use of degree symbols after the numbers.

The best way to understand how widely these three scales differ is by creating your own benchmark and comparing reasonable temperatures across those three scales. A good, subjective benchmark is room temperature, generally considered to be around 70 degrees Fahrenheit. A person in another country may believe that 70 degrees would be scorching, and that the conditions would be a reasonable 20°C. If you were to ask someone who studies in Kelvin, too, then their interpretation would seem crazy, as well.