Weather 101: The El Niño Southern Oscillation

A climate phenomenon originating in the Pacific Ocean is one of the most closely-watched winter weather tools in our neck of the woods.

This phenomenon is known as ENSO, an acronym for the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. This process describes a cyclic, yet mundane shift of sea surface temperatures off the coast of South America, though this process can change weather patterns across the world. To understand both phases of this cycle, though, let’s get to know how water in this part of the world heats up and cools down.

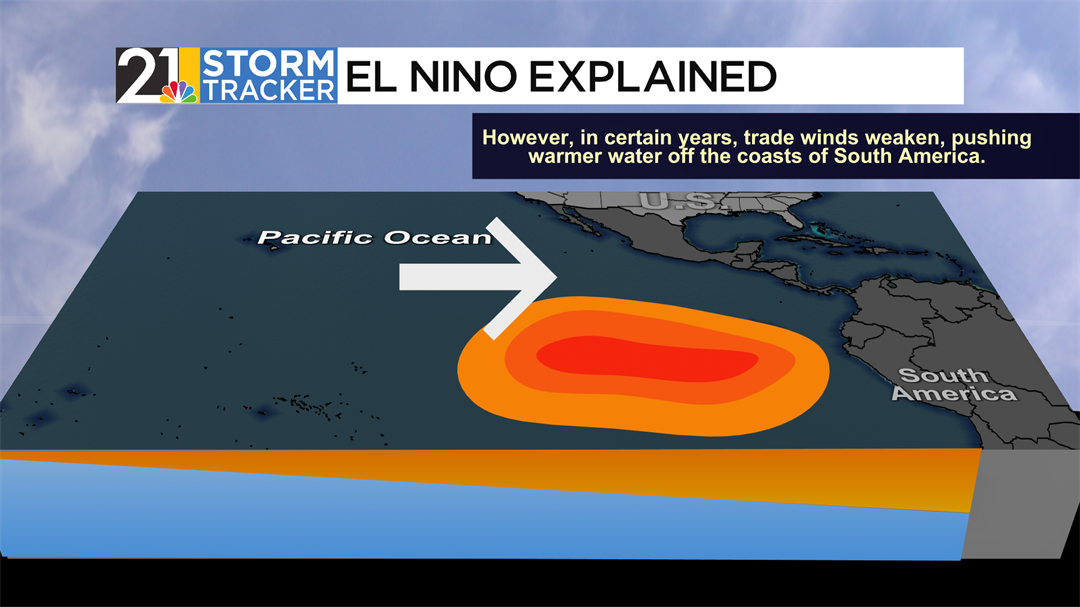

These waters are located off the western coast of South America, around the equator. At this latitude, trade winds blow from east to west (this is opposite of our area, as winds and prevailing weather systems usually come from west to east), or from South America towards Asia. While winds can only blow above water, they can act to move and disturb the oceans below.

Trade winds become weaker in El Niño scenarios. With weaker winds, less water is pushed away from the coast, leaving a large area of stagnant water that can heat up quickly. As a result, sea surface temperatures become higher than average.

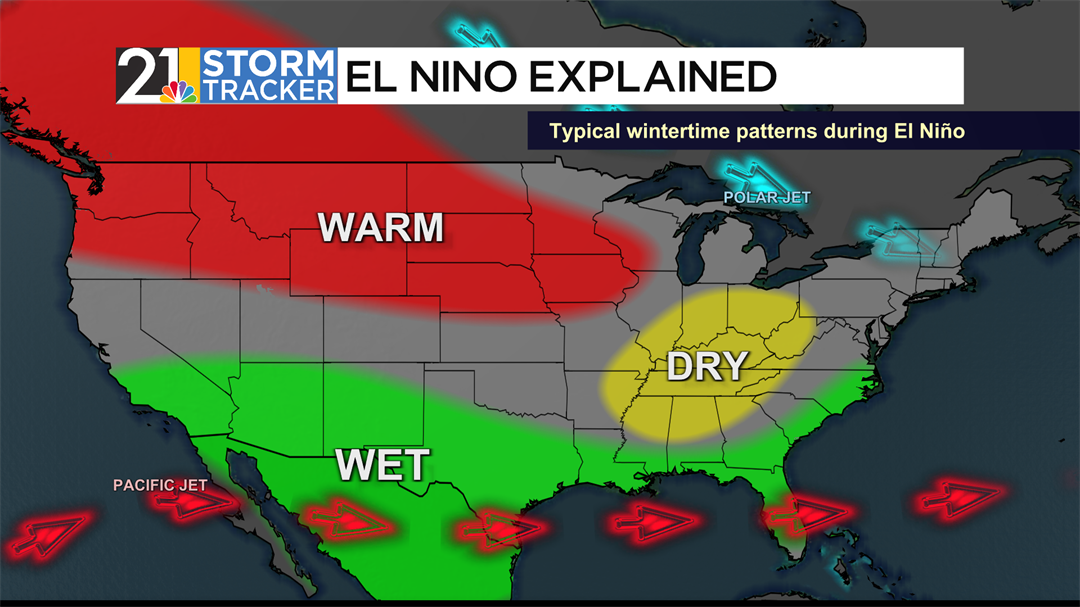

El Niños can primarily impact the jet stream, the conveyor belt of strong winds high in our atmosphere. The Pacific jet stream shifts south and strengthens, steering more storms toward the southern United States and California, often leading to wetter conditions there. The polar jet stream is often pushed northward, leaving warmer, drier winters in parts of the northern and central U.S.

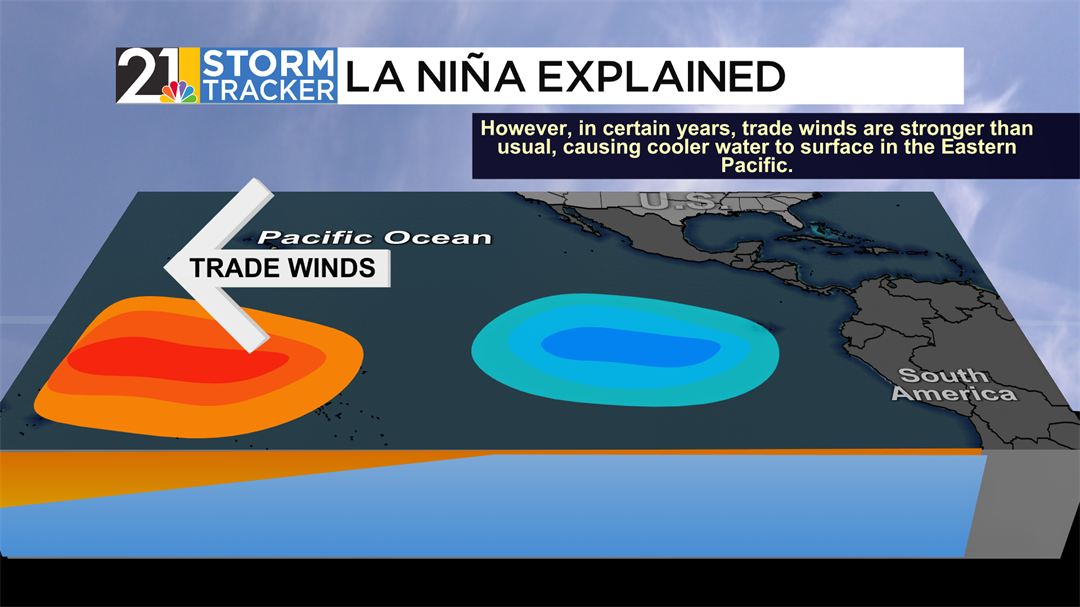

Stronger-than-usual trade winds can cause La Niñas to form. When more fierce winds blow across the Pacific, more water is carried out towards Asia. This means that a greater amount of water must be heated along the same surface area compared to El Niños. Additionally, strong, constant wind can cause upwelling, which is deeper, cooler water rising to replace warm water from the surface. These two factors can cause sea surface temperatures to be below average for a time.

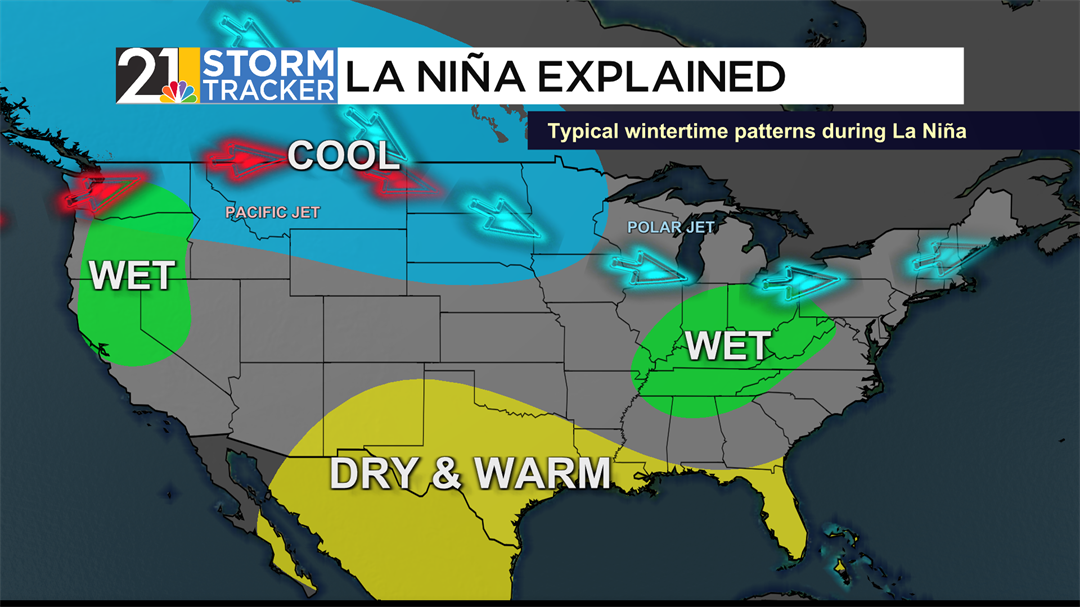

La Niñas act to close the gap between the two jet streams across the United States. The Pacific jet stream, in red above, gets pushed farther north, while the Polar Jet Stream gets pushed south, allowing the northern tier of the country to get colder than average. Winters within the Valley tend to be drier than average under La Niña conditions.

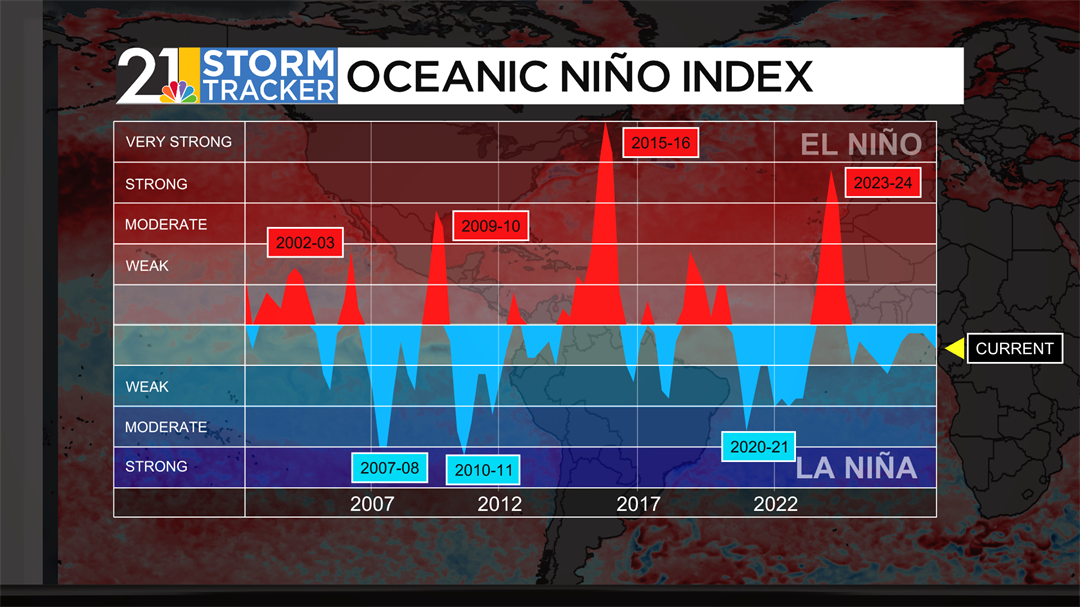

For the ocean to be in one of the two phases, the basin must have a combined sea surface temperature departure of about a degree Fahrenheit for a sustained period of a few months. Currently, we are on the cusp of Neutral and La Niña conditions. The U.S. Climate Prediction Center claims that we are currently in a weak La Niña. Other organizations, such as Columbia’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society, claim the Pacific is still ENSO-neutral.

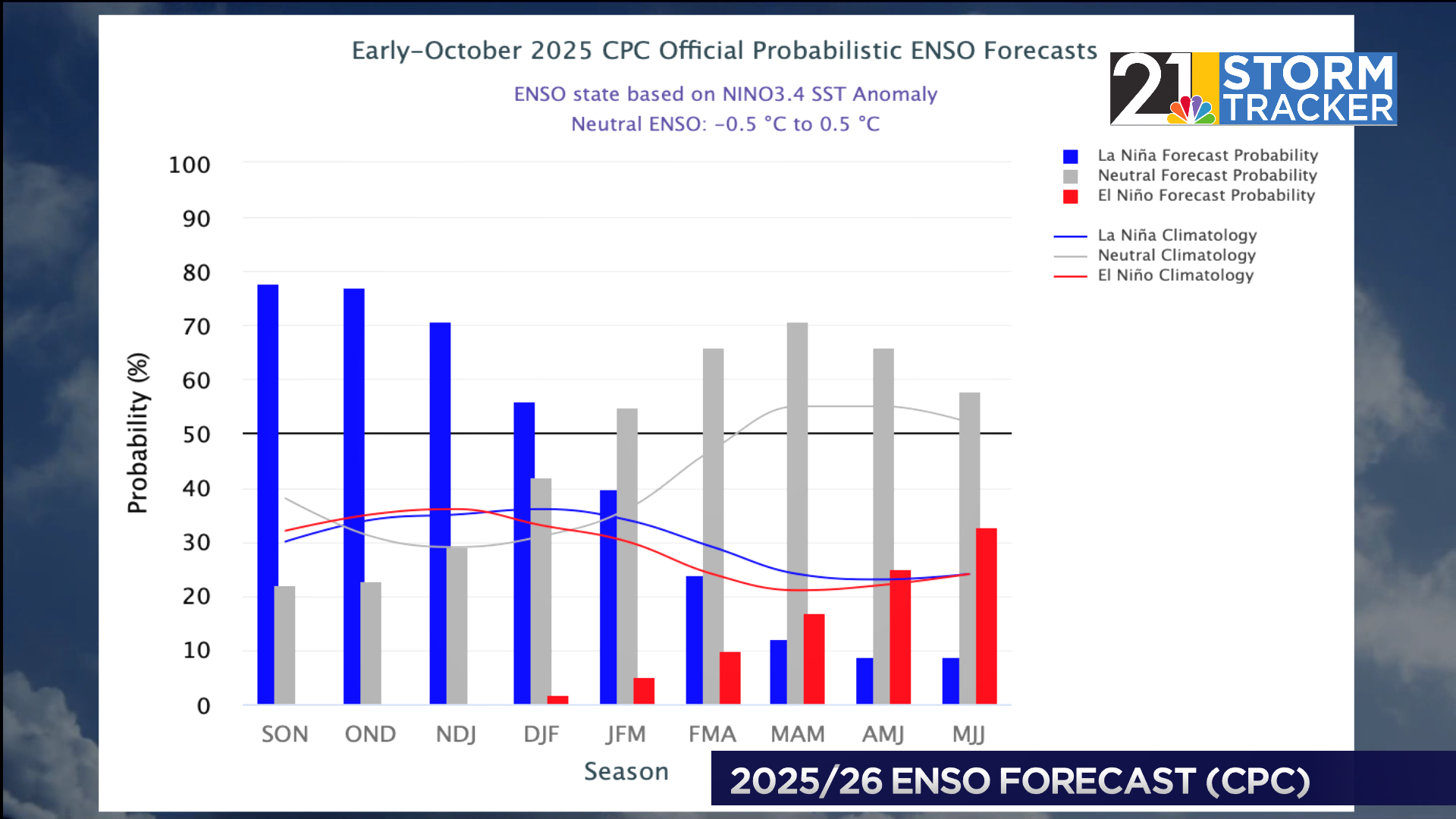

All bodies, though, agree La Niña conditions are becoming more favorable. Attached above is the IRI’s prediction, displaying a moderate-to-high likelihood for La Niña conditions to end the year, though favorability detracts towards the start of 2026.

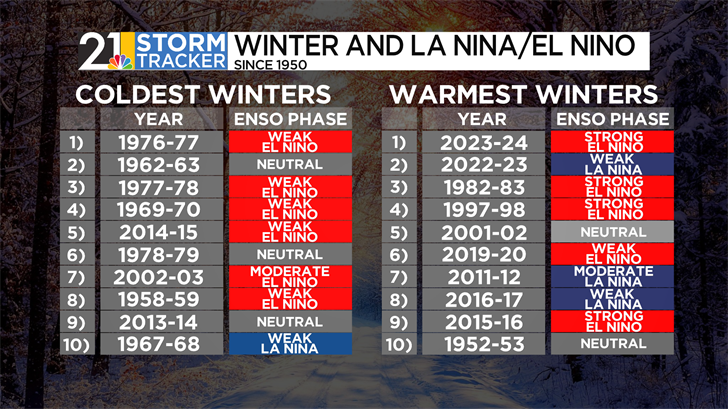

Some of the Valley’s coldest winters have come in years with El Niños present. Six of the ten chilliest winters have either been during a weak or moderate El Niño. However, warm winters can also be seen during strong El Niños, with four contributing to the top ten warmest ones since 1950.

It should be known, however, that The Valley sees more precipitation variance in relation to ENSO. Drier winters are more likely during El Niño years, while wetter winters typically come in the presence of a La Niña.

ENSO is just one of several components to think about when forecasting the winter season. Eric Wilhelm will be releasing his yearly winter weather forecast on Tuesday, November 11th, on WFMJ live, the WFMJ Website, and the Storm Tracker 21 app.