Weather 101: Atmospheric Rivers and the recent California Floods

Although bound under the same American flag, weather patterns in the Valley can differ significantly compared to those on the West Coast.

Those on the shores of California, Oregon, and Washington regularly deal with rainy and dry seasons. Rainfall and snowfall tend to peak in the winter months, when patterns allow for low pressure to sit off the coast. Drier weather tends to rule the summer months, which is consequently when wildfire season peaks.

Rainfall can also be extremely inconsistent on a year-to-year basis. Lake-effect precipitation is not a possibility off the Pacific Ocean, tropical systems rarely track into the western U.S., and strong, cross-country storms tend to develop over the Rocky Mountains, further East.

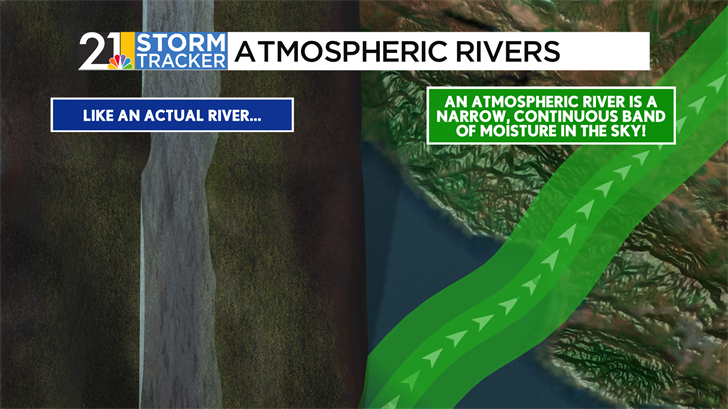

For that reason, the 50 million people who reside in this area look to atmospheric rivers as a strong, impactful source of wintertime rain and snow. Like its surface-based counterpart, these rivers high in the sky contain narrow bands of very strong moisture.

Atmospheric rivers are commonplace around Earth, especially in Mid-Latitude areas such as the U.S. Pacific Coast, France & Spain, and New Zealand. These bands set up around the Mid-Latitudes due to interactions between the jet stream and other surface features we’ll describe in a moment.

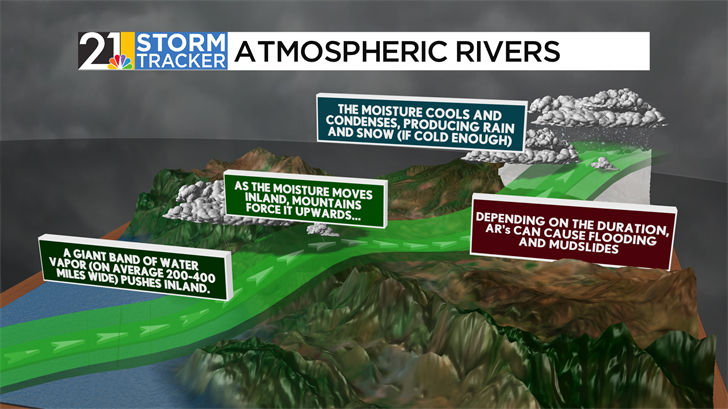

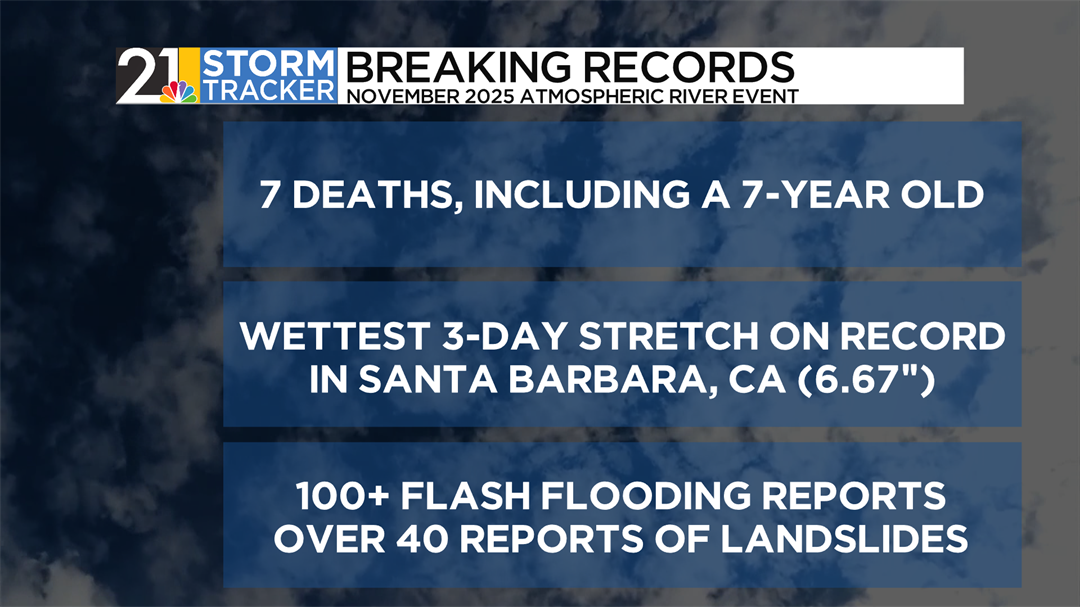

In any case, these bands of rain can be very narrow, with widths of just 200-400 miles compared to a length of a few thousand miles. As these bands push inland, they can interact with ridges and mountains, further sparking rainfall or snowfall. On mountains, feet of snow can fall, and mudslides can be triggered if there is enough rainfall to soften the sloped ground.

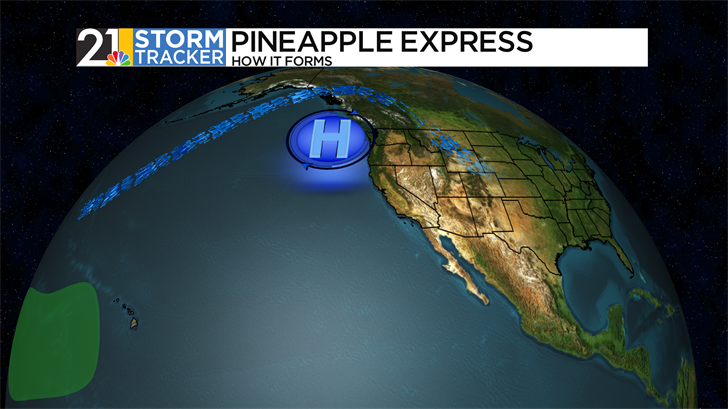

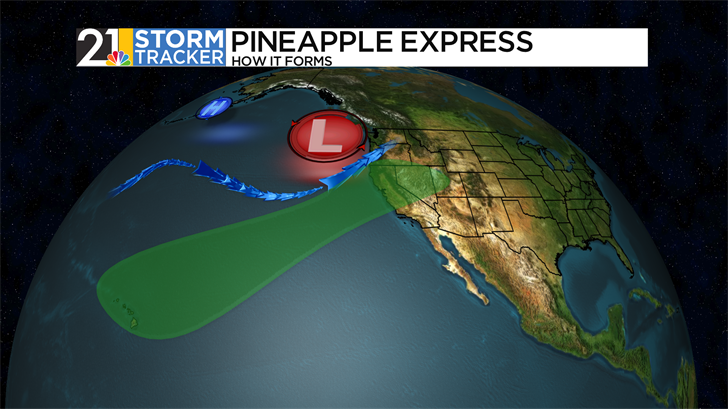

Perhaps the most well-known atmospheric river type to form is called the Pineapple Express. This type of atmospheric river starts sunny for those overlooking the Pacific, as a ridge of strong high pressure typically rules over the Canadian Pacific coast. As high pressure weakens and moves west, however, the jet stream kinks dramatically to the north, and thunderstorms begin to move Eastward off of Hawaii. As high pressure continues to weaken, the jet stream, taking a path of least resistance, bulges back down, forming a trough of low pressure. This acts as a funnel for rain to invade the Pacific Coast. This type of atmospheric river gets its name from the fruit's famous production home, Hawaii.

On satellite presentation, atmospheric rivers look like "conveyor belts” of moisture. Low pressure to the north drags the narrow band of moisture from the warm, sultry tropics up to the Pacific Coast.

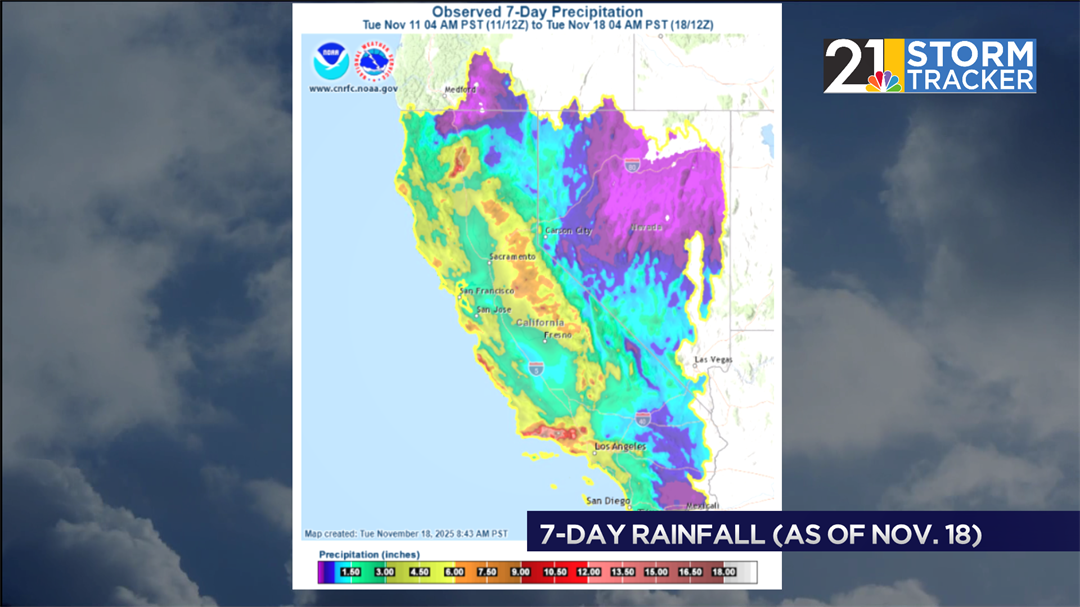

This is exactly what happened over the weekend. Several locations close to Los Angeles received over twice their average monthly rainfall in just three days. Santa Barbara, a bit north of the country’s second most populous city, had 6.67” of accumulation in three days, shattering a record. In addition to mountain snow, over 100 flash flooding events were reported, and 40 landslides, as well. Due to this, at least seven people succumbed to the heavy rain and fierce ocean waves associated with the storm.

Part of why atmospheric rivers are so closely watched is that it has a two-pronged effect. They are usually very impactful, bringing several inches of rain to areas not naturally prepared for heavy events. On the other hand, the absence of atmospheric rivers doesn’t leave many other options for appreciable rainfall to occur in the area. A lack of atmospheric rivers has caused exceptional droughts in California, such as the historic mid-2010s drought, which was coincidentally ended by multiple rounds of atmospheric rivers.

After a strong round of rain over the weekend, Southern California and the rest of the Pacific Coast will face another round of precipitation, though less impactful, before dry weather is expected after the coming weekend.