Weather 101: Sudden Stratospheric Warming and the Polar Vortex

The term polar vortex has been recently attributed to sustained, bone-chilling cold events.

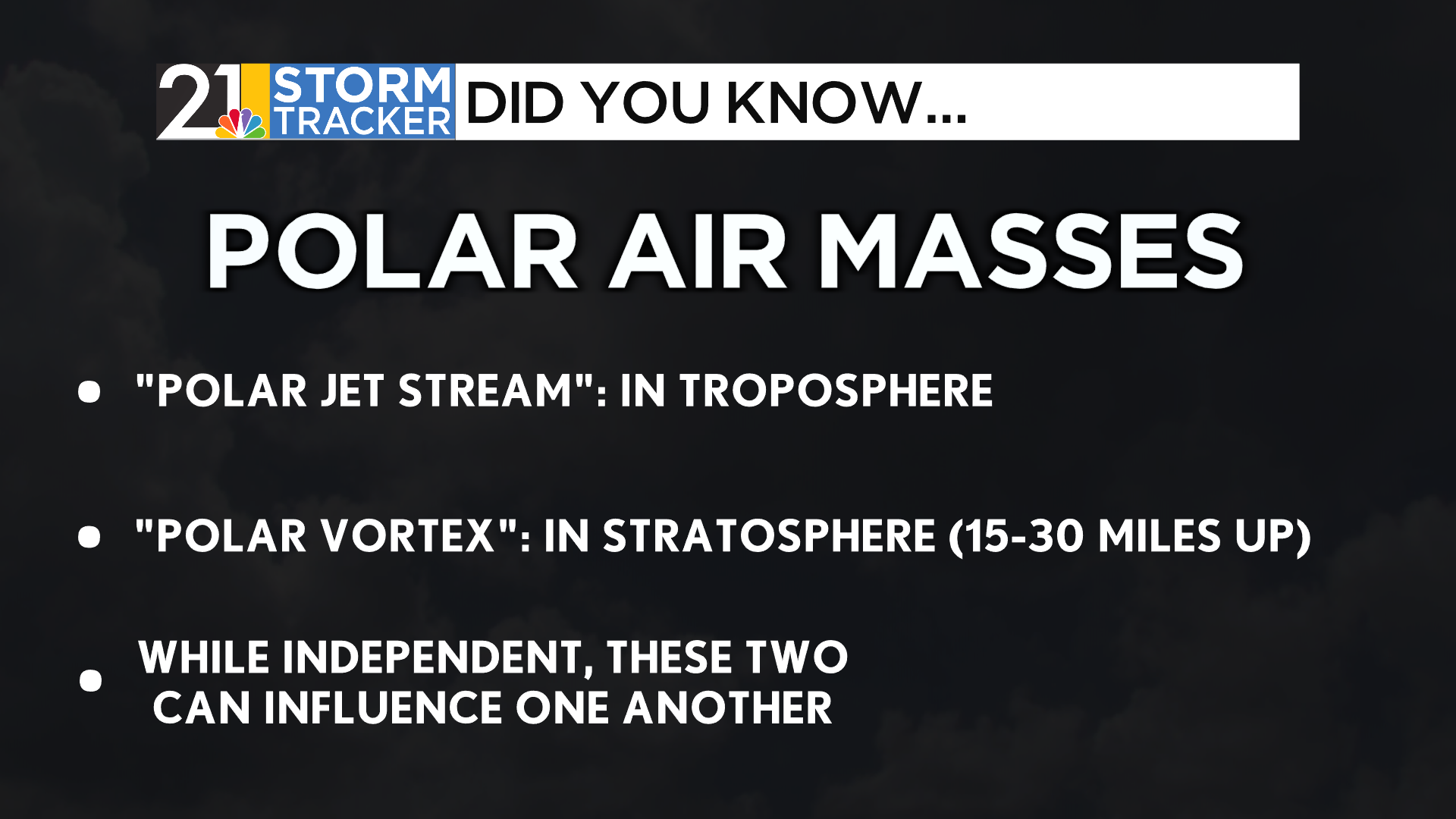

While certainly good language to warn an audience, the wording is technically incorrect. That’s because that mass of air exists in the stratosphere, a layer of atmosphere over 10 miles above our heads.

The polar vortex, however, can influence the movement of the polar jet stream, the conveyor belt of air moving across our troposphere, the layer of atmosphere closest to our surface.

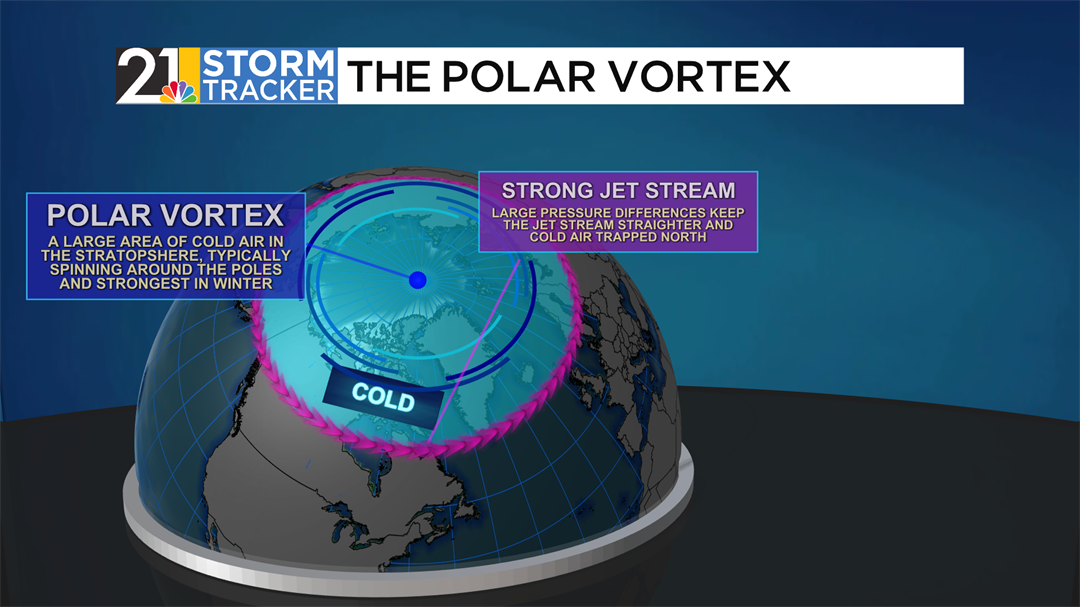

In reality, the polar vortex acts as a sort of boundary between cold, stagnant air and warmer, fluid air near the North and South Poles. It is at its strongest in each hemisphere’s wintertime, when sunlight cannot reach high latitudes. When the polar vortex is in a stable condition, the boundary between air masses is firm, and the polar jet stream maintains a relatively straight-line pattern across the globe, known as zonal flow.

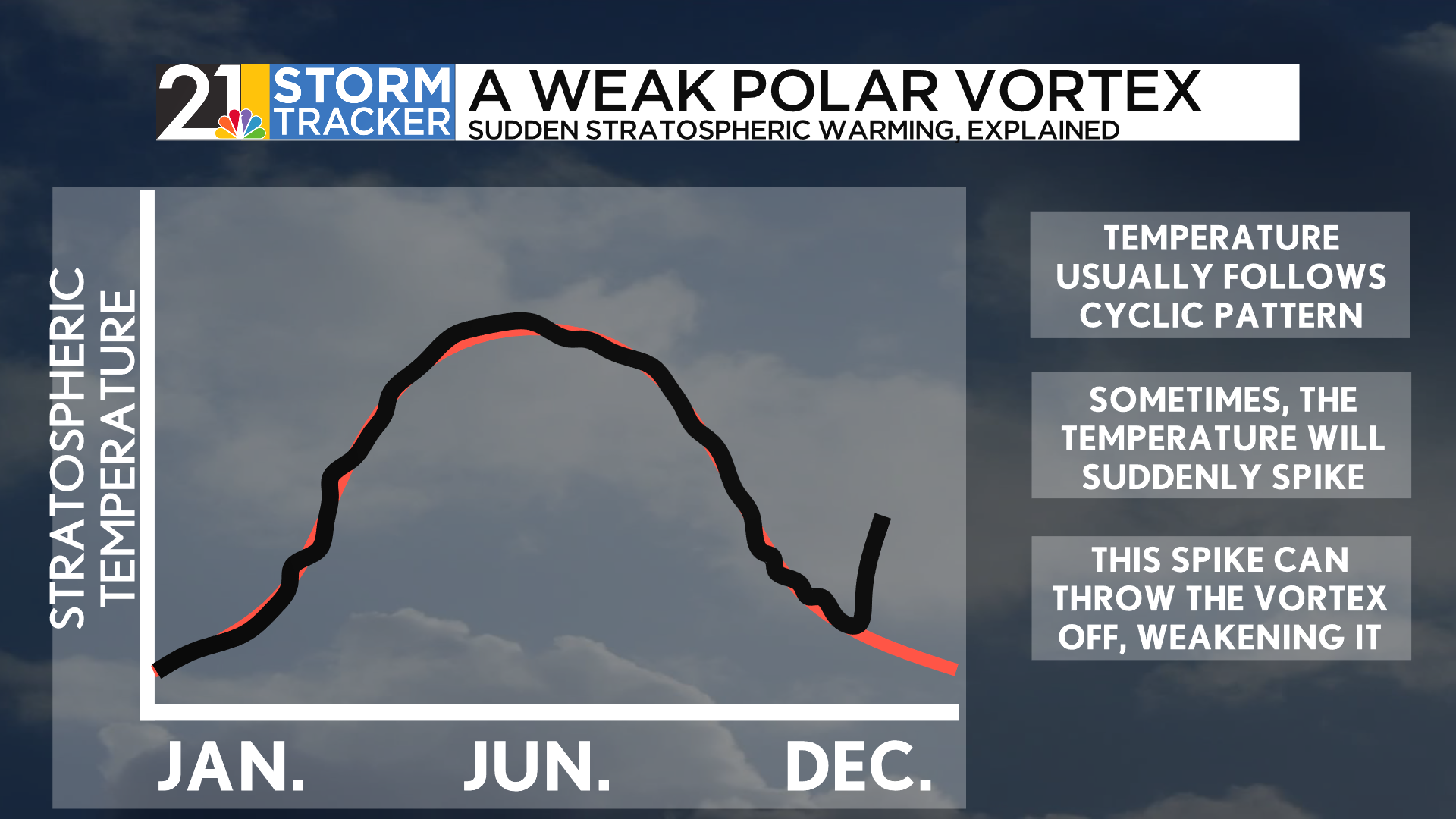

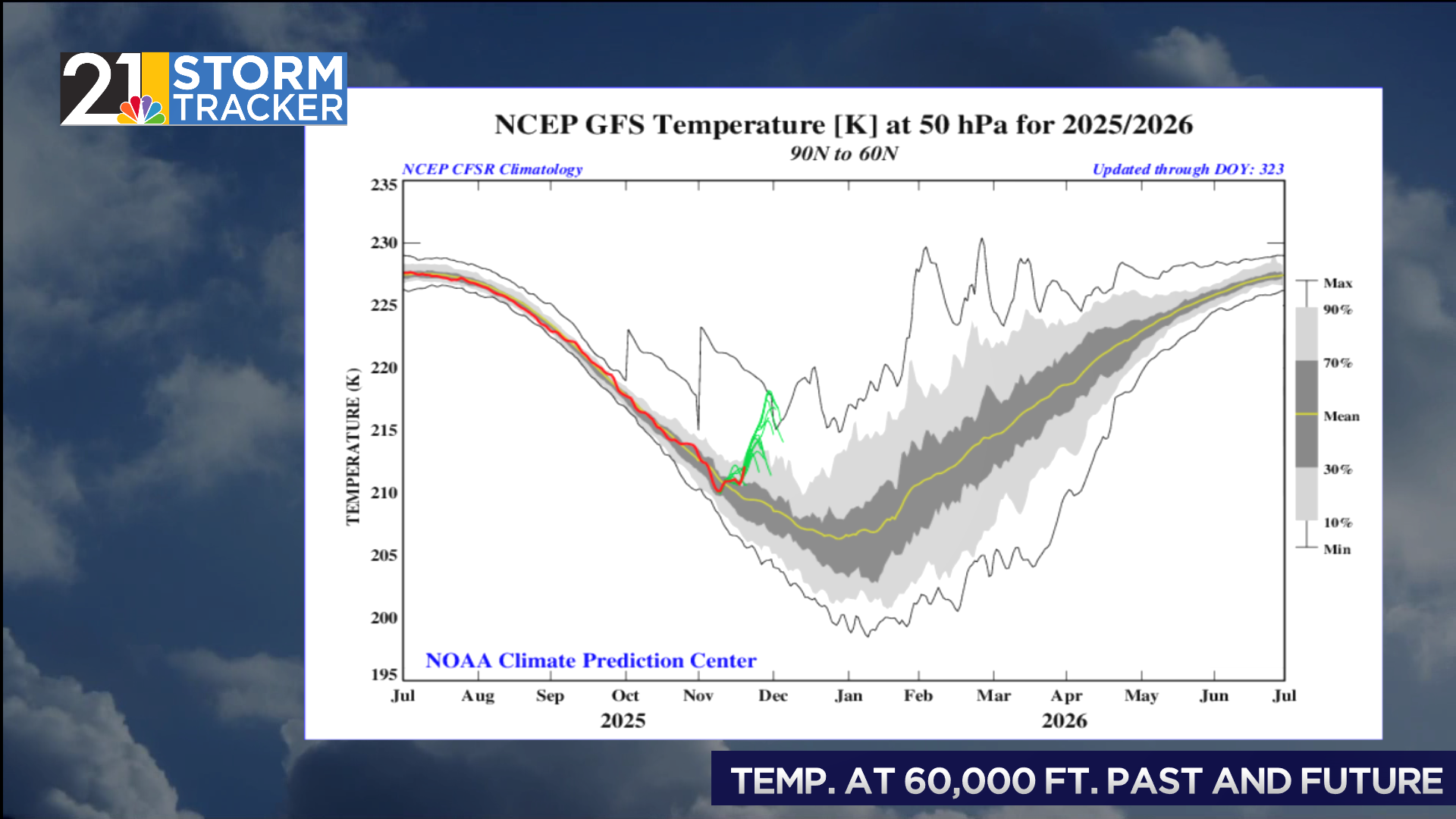

The average temperature of the polar vortex usually follows a cyclical pattern throughout the year, with the peak occurring around -50°F in the summer months, while it can drop as low as -100°F during the winter. However, sudden stratospheric warming events (SSWs) can abruptly increase the temperature of the vortex and weaken it. During these events, the temperature of the vortex can increase by 40°F in the span of a few days.

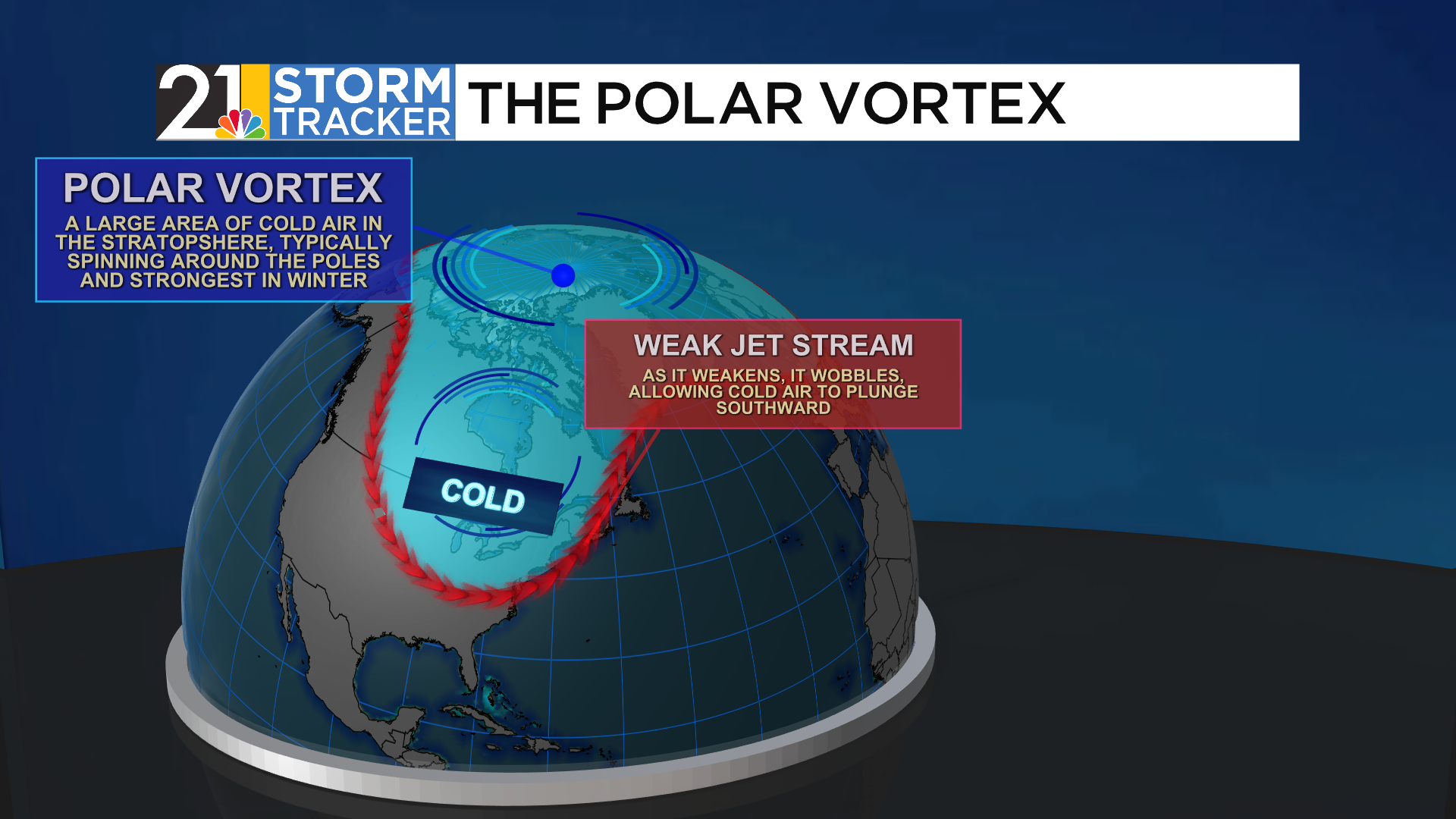

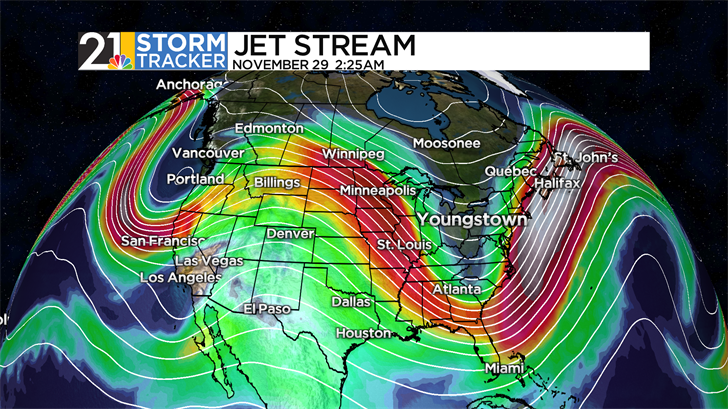

Occurring about once every two years, SSWs can seriously damage the structure of the polar vortex. The circulation can break down, with stratospheric winds shifting from westerly to easterly. As winds break down, the chunks of cold air can even break off and move equatorward. A weakened polar vortex can cause the polar jet stream below to become incredibly wavy and erratic, a regime known as meridional flow. In layman's terms, the jet stream- rather than easily flowing from West to East, can buckle in spots, dragging unseasonably warm air northward and moving anomalously cold air towards the south.

Currently, the Polar Vortex is declining in temperature, a standard for late fall as sunlight lessens around the Arctic. However, temperatures are expected to climb around 20°F in the next week or so, an uncommon feat this early in the winter. Some model projections even think that the polar vortex will be warmer than ever recorded in late November.

With this being said, an otherwise quiet current setup could become very action-packed by the time November comes to a close. Currently, it’s too early to pinpoint temperatures or conditions, though early upper-level models show the jet stream becoming much more wavy just after Thanksgiving, after a rather zonal period beforehand. The position of this jet, while hard to decisively determine as well, will matter as well, determining those locations getting a strong chill and the locations getting very mild air.

So while you can’t singlehandedly blame the polar vortex for bringing abundantly cold conditions to our area, you can thank SSWs for getting the jet stream wavy and active, propelling cold air all the way down from the Arctic.